London (STN) to Bucharest (OTP)

Sep 5, 2024

Sep 5, 2024

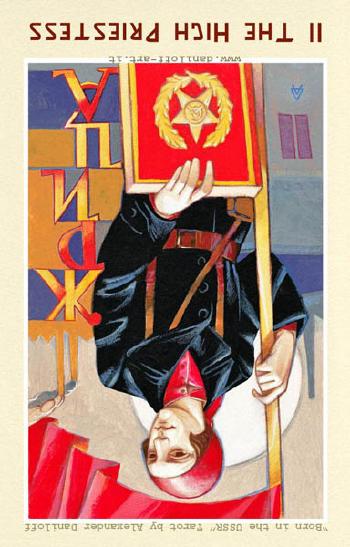

Alexander Daniloff

I’ve spent the last three weeks rambling around England a bit, prepping myself for a busy September. I somehow signed up for three larps — one at the start of September, one at the end, and one in the middle — and I know the best way to ride them out is to try and relax as much as possible.

I’ve been relying on England’s rail network to get around, and it’s still the same as it ever was; expensive, confusing, and inconvenient. You’ll do all right if you’re on a direct and busy route — London to Edinburgh and London to Birmingham are generally tolerable — but the prices and the number of required changes get jacked up pretty quickly, especially if you’d just as soon avoid transferring in London.1 And it’s all very hard to make sense of, even if you’ve got a lot of experience. On my way back towards the West Midlands from Portsmouth I caught the train to Stafford from London Euston only to discover, as it was leaving the station, that I had caught the wrong train to Stafford. There are two entirely different train companies running that route, the tickets are not interchangable, and they always seem to schedule trains leaving within five minutes of each other. It’s an incredibly easy mistake to make.2 In this case, luckily, I was able to hop off the train at the next station and wait five minutes for the train I was supposed to be on, before they checked my ticket and demanded I purchase another one.

I’ve been catching a lot of connections through London, and late arrivals and early departures means I’ve been forced to find cheap overnight digs, which is a fool’s errand in the best of times. Out of desperation I booked a room overnight at Generator, a hostel charging £40/night near Euston.3 Reader, it was wretched. Steel bunk beds and plastic mattresses I was prepared for — I just needed a place to crash for six hours — but there weren’t even any curtains for a modicum of privacy. I was disappointed but not surprised to discover there weren’t any outlets for electricity.4 But the worst part was they don’t provide lockers with locks; I wasn’t going to shell out money to buy an overpriced lock from them, especially since I’d just end up throwing it out when I left, so I ended up sleeping fitfully while sprawled across all my bags, worried I’d wake up to find my wallet or cell phone missing.

I realize I’m not the target market here, but it really did feel dreadful. On my way to Stansted to fly out I ended up staying in London again, but this time I rented a dorm room from the London School of Economics for the night for £80. And it wasn’t amazing — there was a shared toilet and shower down the hall — but you got a private room with a door that locks and proper outlets and they made the bed for you and provided a clean towel. If only that were available when school was in session.

While I was perambulating I swung down to Portsmouth for a long holiday weekend. I have a friend living there who’s very close to the parkland where a three-day music festival called the Victorious Festival is held. We got tickets for the Friday, largely because the headliners were Snow Patrol and Fatboy Slim, and I had heard of them.5 I’ve never followed music very closely; I found the ubiquitous top-40 radio format when I was growing up grating and repetitive, I’ve never danced, and I’ve never been keen enough on crowds to go to many festivals so I never really got exposed to a particularly broad swath of what’s out there. But there’s a difference between being apathetic towards something and being hostile towards it. While I was living in New York I had finally fallen into a kind of rhythm of going to various shows around the city, and I’ve kind of missed it while I’ve been traveling. So I was happy for the opportunity to check things out for the day.

Portsmouth’s where a large portion of the D-Day invasion kicked off, and the festival grounds encompass a museum and one of the landing crafts, both of which are open to tours during the festival.6 The museum in particular still tilts, understandably, towards hagiography7 but it was quiet and air conditioned and a somber if jarring contrast to all the music happening outside.

Friday turned out to be the right day. It was sunny and warm8 and my friend and I spent most of the morning and afternoon wandering around the grounds, just soaking up the atmosphere and stopping to catch a few acts here and there. I had spent the week leading up to the festival listening to most of the bands which were playing and I really got kind of enraptured with Baby Queen, who I guess I’d describe as bubblegum pop by way of Nick Cave. I liked their album so much I only stayed for a few songs of the Snow Patrol set before hiking the 20 minutes across the fairground to catch Baby Queen’s whole set. Zero regrets, even if my friend and I were decades older than the rest of the crowd.

We finished the day with Fatboy Slim. And if everything up to that point was everything great about music festivals, that ending highlighted everything that’s terrible about them: it was cold and starting to rain, there was nowhere to sit, you had had to choose between a terrible view of the stage with at least a little room to breathe or a mediocre view of the stage crammed into a crowd that was packed cheek-by-jowl. The music was great, and I’d happily have spent another couple hours listening to it if I could have done it from a Barcalounger. I’m happy to have caught as much of it as I could. But by then my back was killing me and I could only stand for about an hour of the set, we left with 30 minutes left to go and just managed to walk off the festival grounds and catch a cab before the heavens opened up and soaked everything.

The next day was spent hitting every charity shop in Portsmouth and picking up three costumes for my upcoming larps. I’m lucky that they’re all pretty simple with a lot of overlap between them.9 I’ve managed to cram a pair of boots and a pair of shoes in my carry on, alongside a second-hand cardigan and a jacket and a pair of wool trousers and a white collared shirt.10 With all that sorted I was ready for the first of the three larps I’ve got lined up, and having just wrapped it up yesterday I now find myself at Stansted, flying off for a brief Romanian interlude before returning to the UK for the next one.

I ended this stretch in the UK by playing Welcome to Whisper Bay, a three-day, 60-player larp set in the early 90s and based on TV shows like Twin Peaks and The X-Files. The general vibe was conspiracies within conspiracies. In the game Whisper Bay is a kind of quaint, quiet seaside town in Cornwall11 and stuffed full of exactly the kind of mysteries and secrets and crackpots-who-are-on-to-something you’re imagining. It’s not a genre I feel a particular affinity for12 but it has the advantage of not being done to death, and novelty counts for something.

I was most curious how they were going to handle the revelations in the game. The game was advertised as “mostly transparent,” with most character’s secrets known to everybody, and I was somewhat surprised to discover that was effectively mandated by having major spoilers included in the publicly available character blurbs.13 The game was positively overstuffed with factions and plotlines, which I don’t feel particularly bad about spoiling since most of it’s spoiled through the process of choosing a character:14 there was the de rigueur cult trying to summon the Old Gods, a GCHQ listening post, a group of alien hunters trying to establish contact, a collection of archeologists digging around for artifacts, a drug ring, and a group of investors with heavily implied demonic powers. This is all layered upon a parish council, a computer club, a Women’s Institute, a number of unsolved disappearances and murders, and a group of sullen teenagers.

I was playing an out-of-work miner who was also Soviet sleeper agent in a spy ring operating out of Whisper Bay who had helped cover up a murder and more recently beaten up someone who had threatened the spy ring and subsequently gone missing and furthermore I was possessed by one of a number of spirits who had been feeding off of villagers for years and were hunted by yet another group of villagers dedicated to fending off the threat. Any one of these plots would have been sufficient for most larps. The one I ended up latching onto was one where my character had found half of an artifact of great power; my driving purpose — as written into the character sheet — was to find the other half of the artifact and activate something I imagined would usher in a glorious Communist paradise.

This all went off the rails fairly quickly, and the ways in which it went off the rails highlight some of the pitfalls of running a “mostly transparent” game. It turns out the organizers only meant transparency between the players. The information I had was both intentionally misleading (the artifact in question was a technological “Doomsday Device”) and deliberately wrong (there were five necessary pieces to assemble the device, not two).

Based on my character sheet, I had thought this was a plot involving my character and maybe a few other people, but the Doomsday Device was something that touched a lot of players, and I would have seriously recalibrated how I approached it if I had known that going in. But I didn’t have any way of knowing that going in. Even the short blurb in the player materials wasn’t available to me, because it wasn’t called a “Doomsday Device” on my sheet so I wasn’t aware the write-up was relevant. In retrospect I needed to sit down early on in the larp with all the relevant parties and talk about the plot. But despite the transparency of the game, that simply wasn’t possible. The organizers chose to withhold the identities of those involved in the plot, so I had no idea who I even needed to negotiate the plotline with.

So I spent the majority of my game having what ended up being a frustrating time trying to track down an artifact that wasn’t an artifact, that had far more pieces to it than I was aware of, that had no information available to narrow down what I was looking for or where I should be looking, and which unbeknownst to me had several players working specifically to ensure I wasn’t going to be able to succeed.15 Maybe even all that would have been okay, if some of the minor plots I was involved in had some kind of payoff. But I never ended up getting questioned for the murder I had helped cover up, nor did I get pulled in about the missing person I had roughed up. All my external character contacts were involved in their own plots. And the one in-character thing specifically written into the game for me ended up being a complete shitshow.16

All in all, a disheartening game. It was salvaged a bit by having some great players in the Soviet spy ring; I really enjoyed my scenes with them. But none of the rest of the game ever jelled for me. For a lot of players that wasn’t the case. They found their characters pointed in interesting and useful directions and were able to guide their plots in meaningful ways, hopping from thread to thread as they found one way or another blocked. But it seems like that was as much luck as anything. Looking back, I’m just mystified trying to figure out what the intended payoffs for my plotlines were intended to be. Because I certainly didn’t find many of them during the game.

Footnotes

1 Transferring in London almost inevitably requires getting in at one station then catching the Underground to an entirely different station before continuing onwards, which is a massive pain in the ass even with minimal luggage and ample time. It also means having to pick up physical tickets at the station, since the transfer is included in the ticket price but the Underground isn’t integrated into the electronic ticketing system.

2 Trains are listed on the main board according to their final destination. Trains are listed on your tickets by your destination and the final destination of your route doesn’t appear on it at all.

3 I was arriving at 11pm and needed to head back out to Heathrow the following morning, and the cheapest alternatives I found started at £170.

4 In this day and age, USB connections just don’t cut it.

5 Fatboy Slim, in particular, was inescapable during the late 90s. I imagine the aliens living 25 light years away are only just now becoming thoroughly sick of Praise You.

6 The museum is home to The Overlord Embroidery, a retelling of the story of D-Day in appliqué as a kind of callback to The Bayeux Tapestry. It took the Royal School of Needlework five years to complete, and in its finished state it’s nearly as long as a football field. It’s almost certainly worth a visit if you’re into sewing. Or tapestries. Or the admittedly small overlap between war history and the decorative arts.

7 I find World War II particularly difficult to assess historically. World War I was marked with staggering incompetence all around and the Vietnam War’s been litigated and relitigated to death, so I feel like I’ve got a decent grasp of those conflicts. But I have trouble seeing through the wartime propaganda of the Allies, because the Nazi’s were genuinely such cartoonishly evil enemies. In hindsight, a lot of the propaganda feels understated, if anything.

8 Saturday was rainstorms, although I still might have liked to catch the Pixies’ set in the evening.

9 One working class early 1990s, one dull WWII-era wartime, and one 1970s which could have been batshit crazy but all we’re required to bring is a base — trousers, collared shirt, and boots — and they’re providing the rest.

10 White shirts are bizarrely hard for me to source, since I don’t own any and they’re in notably short supply in thrift stores.

11 I’m not entirely sure why it wasn’t set in the United States; the genre is pretty firmly American Gothic and the closest UK analogue is folk horror, which this wasn’t.

12 I’ve seen at most a half-dozen episodes of X-Files and know Twin Peaks almost exclusively from memes.

13 I’m used to “fully transparent” games allowing players to opt in to reading all the characters but not requiring it, so you could choose what level of spoilers you wanted to engage in. Putting them in the blurbs effectively forces everyone to read them all.

14 But if you’re hoping for a rerun and want to find it all for yourself, be forewarned.

15 There’s a fundamental conflict in having a larp based on transparency and negotiation and having plotlines resolved by in-game props. The various pieces of the doomsday device were constantly being stolen and restolen, and often you’d steal something to discover someone had beaten you to it and left you the empty box.

Transparent games tend to expect players to sit down and talk through how this plays out — does it make for a better story if your character steals this from mine or if my character steals this from yours? — but here you have a situation where neither Player A nor Player B even knows about each other. By necessity, possession of the prop trumps the negotiation.

16 Although most food in the game was provided by an in-game cafe where you could reliably get something to eat at any reasonable hour, the organizers had asked for volunteers to prepare meals for other players, I assume to increase the feel of village life. I volunteered, and ended up being assigned to host a “socialist tea” for two hours the second day in the evening.

To start with, we had no idea how many people to expect; there were two of us who were cooking dinner and one other person assigned to eat with us, but there were also 40 players and NPCs who were invited, so we needed to potentially prepare to feed upwards of three dozen people. I requested enough ingredients for 12. Once we arrived I realized I had forgotten some crucial supplies and had to take a half-hour off game (with the eternal forbearance of one of my coplayers) to run off to Tesco and buy ingredients out-of-pocket. When I arrived at the kitchen early to start cooking so it would be ready on time, I discovered another player there frying up venison steaks for themselves and had to wait for 20 minutes for them to finish (and had to clean up after them, since they decided to skip out on washing up) before I could start. I spent the next few hours gathering the items for the tea and making food and setting everything out and sitting around waiting to host dinner. And not a single person showed up to eat it.

If you’re organizing a game, and you’re thinking of asking players to volunteer a significant amount of time and energy and labor to make your game better, I’d have thought you’d have at a minimum ensured there’d be some sort of payoff or reward for that effort. I was wrong.