London (LHR) to Berlin (BER)

Dec 28, 2023

Dec 28, 2023

Eunice Choi

It’s almost always a mistake to book a flight ridiculously early in the morning, and having that flight get subsequently canceled is doubly painful. Had I known I was going to be traveling to Berlin I might have booked a flight out the same day I landed in London.1 By the time I did have New Year’s plans I had already bought theater tickets for the day. So I figured I’d stay for the night in the hotel by the airport and booked a cheap flight for 7:15am the next morning. But of course it’s an hour from central London to Heathrow on the underground so I wasn’t back in the hotel until nearly midnight, and you’ve got to be up by 5:30am to get to your flight when they start boarding.

But there’s been a disruption because of storm somewhere in the system, and the airplane never made it to Heathrow, so I got a rather terse text this morning announcing my morning flight was canceled at 5:45am. This is merely annoying for me — I got the option to rebook to a flight at 4pm, and I’ve no need to be in Berlin early — but I managed to sync up with a friend who was booked on the same flight and they needed an earlier flight. So there was a comedy of errors where we tried to walk over to talk to a customer service representative for British Airways only to discover they only exist airside after security, so first you need to use a computer to rebook your flight and check in before you can talk to them about rebooking your flight. I had already done so, my friend was unable to book the 4pm flight from Heathrow but was able to book a 10:50am flight from London City Airport, and when I finally got through to a customer service representative about switching to that flight so we could fly together I was told there was a £50 change fee.2

It’s probably for the best. I didn’t particularly fancy dragging my ass across the breadth of London to make the other flight, and it’s an E190 which only has four seats across so it’s worse for turbulence. But I would have made that exchange to spend time with a friend, and at a minimum that decision should be mine to make. I think that’s the least I could ask.

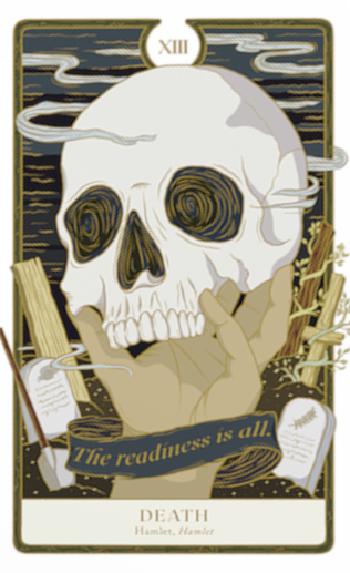

I stayed in London for the night to see The Motive and the Cue, a new play recently transferred from the National Theater to the West End. It’s a love letter to the theater, specifically the 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet directed by John Gielgud and starring Richard Burton. The original was a sensation, buoyed by Burton’s celebrity and recent marriage to Elizabeth Taylor; it ran for 137 performances, a record for Hamlet, beating out Gielgud’s record-setting performance in the lead role in 1936.3

Time hasn’t been especially kind to Richard Burton’s Hamlet, nor Richard Burton, for that matter. Their reputation is as an often great but largely inconsistent actor, and their career is known as much for its misses as its hits. In other words, it’s a rich backdrop for a play that’s interested in the intersection between art and celebrity, as well as the ways performers are forced to bridge the gap between the actor and the character. The Motive and the Cue covers the time from the first readthrough to just before the curtain is raised on the opening night. It’s largely a three-hander. Burton’s struggling to find an authentic voice for Hamlet while Taylor — the bigger star — tries to subtly guide the production to a successful premiere. But the heart of the work is Mark Gatiss as Gielgud, suffering through the doldrums of their career and worried they’ve slid into irrelevance. Gatiss invests the role with a quiet dignity, lonely but proud, an emissary from the past trying and failing to connect with the present.4

For a theater geek with a taste for history, the whole thing was irresistible. Gielgud represents the classicists, while Burton represents the modernists supplanting them. It’s actors playing actors rehearsing a play which itself famously contains a play. The peculiar mix of braggadocio and insecurity common to actors is instantly recognizable. My friend said they couldn’t think of another work that was so obviously in love with the theater.5

If there’s a flaw in the writing, it’s that it goes too easy on the leads. Burton was famously an asshole, and there’s just a single scene of that, quickly resolved. Burton’s marriage to Taylor was notoriously rocky and there’s the barest hint of it. The same is probably true of Gielgud as written, but Mark Gatiss finds a touch of cruel wit and insecurity within the character, injecting Gielgud with the kind of flawed humanity which makes them feel lived in.

It was a thoroughly enjoyable night out and a good reminder of everything I love about live theater. Being without a home has left me unplugged from any local arts scene. I’m going to have to think about ways to remedy that.

Footnotes

1 Or, better, just flown directly to Berlin, if the cost was comparable.

2 I am increasingly infuriated by customer service agents who constantly say they can’t do things when they really mean they won’t do things. I know it’s well within their capability to accommodate the request — presumably there’s a small army of functionaries doing just that somewhere in this airport — and their refusal to do is is strictly because they think they can wring an extra chunk of change from me for doing so.

If you haven’t booked tickets together then the system can’t guarantee you’ll both get bumped to the same flight, which would otherwise be a trivial request for a human to accommodate. Companies increasingly offload these kind of tasks to limited, badly designed systems and then hide behind the limitations of the system to justify bad service.

3 For comparison, Cats would run for 17 years and 7,485 performances.

4 If you’re picking up on some parallels with Hamlet you’ll be delighted to know Gielgud provided the voice for Hamlet’s ghost in the production. Between that and Burton’s alcoholic father there’s a lot of daddy issues going on.

5 I’d probably say Noises Off. No matter how funny a production it is, it’s always felt like it must be twice as funny to the actors in it.