London (LGW) to Edinburgh (EDI)

May 26, 2019

May 26, 2019

I’ve booked about a month of travel around the UK, with about ten days in England and the rest in Scotland. The scheduling was a bit loose; the broader reason for being in the UK is that it’s not Schengen.1 I deliberately left last week open in case a last minute ticket opened up for All For One, a Three Musketeers inspired larp run over last weekend in Wales. And a ticket did become available a couple weeks ago. So here I am.

I flew into London moderately late on Wednesday, and immediately caught public transportation2 out to a friend’s in the West Midlands. The next morning I stopped by Stratford-upon-Avon, rented a costume from the RSC,3 and made it down for the start of the game on Thursday. I’ve been crashing with my friend since All For One ended on Sunday, and since Thursday I’ve just been bumming around London.

When I was first planning all this Richard Shindell, one of my favorite singer/songwriters, announced he would be playing a few solo concerts in the area. The one which fit my plans was held last night out by Gatwick. Thirty people were there. It was sold out. It turns out to be a concert series held by a couple in the sunroom out back of their house in the suburbs. So my last night in England I got to hear one of my favorite artists sing for two hours, acoustic, unamplified, at about an arms-width away.

I had been wanting to play All For One since it was announced. The organizers had a reputation for pulling off crazy effects and immersive set pieces, and the hype was enhanced by their relatively small player count ( All For One had about 35 players) and their refusal to do reruns. I was disappointed but not particularly surprised when I didn’t get a spot in their lottery.4 But on the advice of a friend I put myself on the waitlist and arranged my travel through England to coincide with the game, and sure enough a spot opened up.5

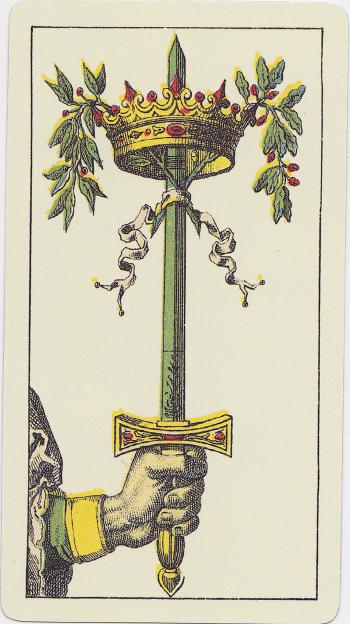

All For One is a larp based on The Three Musketeers. More specifically, it was based on the 1970s swashbuckling movies about The Three Musketeers. The game was played in a beautiful historic house out in Wales.6 It was set roughly fifteen years after the events of the book; the training academy had been shut down because of scandal and only just reopened with D’Artagnan now leading the cadets. King Louis XIII and Queen Anne were still in power, and both Richelieu7 and Mazarin were lurking around. Some tweaks were made to the history — both Constance and Milady had survived8 and both were present.

The players formed the cadets, organized into five cadres, each consisting of six musketeers and a servant. I was in Cadre Verte, traveling actors who happened to be staying in the same inn as the original Cadre Verte on a mission for the Queen when they were poisoned by the villainous de Brie. Their servant (noticing we were the same number and bore a vague resemblance to the original cadre) convinced us to stand in for them and carry out the mission with the promise of a sack of gold at the end for us.

The game itself continued at that level of ridiculousness. Lots of doubles, substitutions, outrageous coincidence, and layers upon layers of intrigue. Duels were dueled. Plots were plotted. Identities were identified. Denouements denouemented. Many of the games I play tend towards dark themes, such as horror, violence, oppression, dystopia, and madness. It’s easier to structure emotional play around those kind of things, I think; most “non-serious” games try to be light or zany and (in my experience) often just come across as bad improv, with no depth to the characters and no weight to the action. It was nice to see a game split the difference. You were encouraged to fail broadly — maybe challenge someone to a duel and fail in the most humiliating way possible — but that didn’t mean you weren’t able to make a noble and meaningful stand in the very next scene.

The actual play of the larp was built around the cadre structure. During the day you’d be required to report at various times, with your cadre, to “Latrine Duty” or “Guard Duty.” Latrine Duty consisted of various loosely improvised scenes in a black box theater,9 while Guard Duty would see you tromping through the woods and interacting with NPCs over a set of semi-scripted encounters. For example, the second day found Cadre Verte traveling deep into Spain to recover a Spanish Alchemist who required escorting to a lab in Paris in order to brew a curative for the King at the request of the Queen.10 The first encounter was some Spanish guards, then Constance who introduced us to the Alchemist, then we stumbled across Aramis rooting out heresies, then finally some of the Cardinal’s men in the pocket of our nemesis de Brie.

One of the most fascinating parts of the game for me was the conceit that we weren’t just musketeers in the 1600s; we were film actors playing musketeers. This didn’t have a big effect while the game was running, but the structure of the game often led to downtime for some players while scenes were set up or the sequence for a particular battle was explained, and during that time the fiction of being actors made a lot of sense. The crew walked around in modern brown jackets and addressed us as “The Talent.” They could set scenes and explain away discrepancies without breaking the larger fiction (“Imagine there’s a big castle here; it’ll get added in post.”) We could be told to cut just as scenes started getting boring and reset for a new one. It encouraged you as a musketeer to do big, crazy, ridiculous things since they didn’t need to make sense, they only needed to make dramatic sense.

So we had big, broad characters and were given big, broad scenarios you could chew the scenery of. Literally, in some cases: one of the set pieces was a tavern brawl complete with larp-safe stools and larp-safe benches and larp-safe baguettes and a larp-safe chandelier to drop on people’s heads.11 The other really impressive set piece was an assault Saturday morning by all the cadets to retake our training grounds, lost during the war with the Spanish. Each cadre took a turn taking parts in an overall plan — kidnapping an enemy general, placing explosives, setting off the bomb, and rescuing a previously captured cadre. The active cadre got to be the heroes, while the remaining players all donned Spanish colors and got to play endless waves of enemy forces, mostly bumbling and incompetent, easy to trick with a feint or a cunning ruse.12

All of the game reflected that kind of excitement. There was training on firing black-powder weapons with real, firing black-powder weapons.13 The food was all top-notch, authentic, and prepared from scratch (although the fresh-baked croissants were pushing historical accuracy).14 And Saturday night culminated in a masquerade where (as specified by game rule) you couldn’t distinguish between any two people wearing the same mask. As an experience, the thing was an immense amount of fun.

As a larp, I thought it was a little more mixed. There are a lot of players who had an incredible game. I also know players who it ultimately didn’t work for — including a lot of the members of my cadre. Larps are deeply personal experiences; you have to put a lot of yourself out there, and as a result you often leave feeling very vulnerable and exposed. Spending the time after a game which you didn’t have a great time at listening to other players gushing about how amazing it was can be a miserable, isolating experience. With a bad game, at least everyone agrees. With a good game you didn’t like, you’re alone and there’s often not even someone to blame.

I need to be clear here; you can separate out the experience of the event (which for me, at least, was fantastic) from the experience of the game (which I thought had some issues). I would recommend without reservation any of the games by this design team. That doesn’t mean I wouldn’t suggest changes.

One of the major decisions in larp design is between secrecy and transparency. Games built around secrecy feature lots of hidden information: things only few players know, surprises to be exposed at crucial moments, dramatic reveals to be unveiled at just the right point for maximum effectiveness. Transparent games might have all of the above for the characters, but the players are already aware of what’s going on. Maybe all the character sheets are available before the game to read. Maybe the game announcement mentions the King will be assassinated Friday night, so you should expect to be arguing about the succession most of Saturday.

At its heart, these are style differences, so nobody can honestly say one is definitively better than the other.15 But I don’t think it’s controversial to say that secrets games are much harder to run than transparent games. If the players know what’s going to happen they can be responsible for much of it. They can arrange any props or costumes or research they need before the game. They can negotiate the big reveal with each other ahead of time. And they can tell when the plot is going off the rails and correct for it.

In a secrets game, they can’t do any of that. It’s all on the organizers. That’s great when the organizers are on top of everything that’s happening in the game, and can tweak things on the fly. But we know organizers have limited tools for understanding what’s happening in a game, and are often overworked as well. Very often, things are going to fall through the cracks.

In All For One, my cadre chased down all our plot by Saturday night. We had exposed the crimes of the villainous de Brie, where he announced he had intended to murder the original Cadre Verte and did burn the inn, but had not poisoned them. We had employed a cunning strategy where one of us approached the Queen during the masquerade, disguised as Constance (her agent), and later approached Constance, disguised as the Queen, and definitively ruled both of them out as being behind the plot to poison the King.

And then … nothing happened. We had nobody else to talk to. No one could tell us who devised the assassination plot against the King. No one had any information about who actually killed Cadre Verte. We ended the game without getting any resolution on either plot. For a game that’s not supposed to have winners, it really felt like we lost.

I’m not blaming the organizers for this. I don’t think it’s their fault. I think these issues, or at least the possibility of them, are baked into the design. Larps have hundreds of moving pieces. Many cadres hit their marks, and whenever things started to run off the rails someone happened to notice and fix it. For ours, there just wasn’t someone in the right place to see it.

We found out after the game that the Queen and Constance were behind the poisoning, but had been tipped off about our discovery ahead of time, so they were prepared for our attempt to catch them out. And the person playing de Brie hadn’t been told about the poisoning, so genuinely didn’t think he was responsible.

I’m not saying the game would have been better, for me, if it had been fully transparent. But certainly these problems wouldn’t have cropped up. We could have still had the confrontation with de Brie, but approached him afterwards and figured out what went wrong. After the masquerade we could have negotiated a scene with the Queen, knowing she was behind the plot but having failed to reveal it through play, where we publicly accused her and she blamed everything on Constance.

The organizers apologized for not providing a resolution at the end of the game for us, which was very generous, but I think it’s slightly missing the critique. A resolution would have been nice, but what I think we really wanted was the ability to resolve the plot for ourselves, in play. And that’s really the crux of the matter, of the difference between secret and transparent games. Secrets games can be amazing. But their failure modes are hard. You sacrifice the excitement of surprise by giving players foreknowledge, but in exchange you give them the power to craft their own game.

Don’t take this as strong advocacy in favor of transparency over secrets. There are games for which lots of hidden information is absolutely the right choice.16 Most games are kind of a mixture anyway. But the more secrets you keep from your players, the less information they have to make good choices in your game. Do your best to make good choices on their behalf.

Footnotes

1 With the travel I’ve done and the travel I’ve planned I’m down to 9 unaccounted-for days in the Schengen Area before I run out of time on my visa. I’ll start getting days back in September as the travel I’ve done over the last couple months starts falling out of the six-month window. I still have no idea where I’m spending August.

2 My cheap flight into London landed in Luton, and it turns out to be a pain to get from Luton out west, especially if you’re arriving late, especially if you’re trying to avoid going into London. Didn’t help that the train at Milton Keynes was delayed by 30 minutes.

3 Squeee!

4 There’s been a lot of discussion (and a lot of angst) over the ways larps allocate tickets. First-come, first-served works fine if your event doesn’t sell out, but the international larp community is seeing a lot of games sell out immediately, often crashing websites in the process and leading to a lot of unhappy players. Lottery is probably the only way to be as fair as possible, but itself leads to tricky problems: Can you sign up with a friend? What if there are different tiers of tickets? How much time to you provide for people to pay, and what do you do if they don’t?

5 I’m still a little amazed at how often spots become available last-minute for games; I’m not sure I can remember a single game that didn’t have a last-minute availability. Of course, costuming and preparation all suffer for it, but just turning up and hoping there’s space for you in a game you really want to play turns out to be less risky than you might think.

6 Although to accommodate all the players some of the player base had to stay off-site and some of the player base stayed in tents. Fun trivia: the house had a ha-ha, although no folly that I am aware of.

7 Who was elected Pope over the course of events

8 Notice how both major female characters in The Three Musketeers were killed off by Dumas? Subtle. To the credit of the organizers, the cadets were mixed gender in flagrant disregard for historical accuracy.

9 A projector was used to display various backdrops — a seedy tavern, a sunny meadow, a dusty crypt — and there were various props and furniture that could be conscripted for the scenes.

10 And who unbeknownst (but highly suspected) by the cadre brewed a deadly poison instead

11 The goal of all this was to grab dinner and run off with it; scattered among the various fake foodstuffs to bash each other over the heads was real bread and wheels of cheese and fruit and roast chicken and bowls of cassoulet. You ate as well as you had the foresight to grab things during the fight.

I’d also like to offer my apologies to the NPC whom I bashed over the head with a real bit of brie. I mourned the loss of the cheese over dinner.

12 One cadre ran into place and set out a picnic, revealing their secret weapon: very smelly cheese. The Spanish all collapsed, horrified and incapacitated, and were distracted long enough for other forces to complete their mission. It was that kind of game.

13 I can now legitimately say I’ve fired a firearm, albeit not one loaded with shot.

14 I understand there was a gastronomy society that featured a special meal, including ortolan, complete with the “cloth of shame” to hide yourself from God while you eat it.

15 Not that you’d know that talking to some of the proponents on either side

16 I’m in the process of designing one myself, although I reserve the right to change my mind.