Independence Day, 2020, Galway

Jul 4, 2020

Cristy C. Road

In 2016, shortly after the New Year, a small group of armed militants took over the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in protest of the United States Government. If you watched the news at the time you already know the basic contours of it; they held out for about a month before the government broke it up. One of the protesters died in a standoff, some of the rest were tried on various charges, and a few spent a little time in prison.

They were protesting the Bureau of Land Management. There wasn’t really a coherent set of demands, but most wanted the Federal Government to turn public lands over to the states. Beyond that their expectations got a little squirrelly. There was a vague idea that the states would auction off the land, and somehow this would ultimately restore control to the people. It all kind of fell apart if you looked at it long enough — their worldview didn’t have any real understanding of multinational corporations, so it’s a little hard to square their ideas on property rights with their ideas on local control — but if you looked past the right-wing crackpot conspiracists and sovereign citizen truthers, in a lot of ways they kind of did have a point.

In the very first of the Federalist Papers, Hamilton observes that the United States felt like it was designed to test a proposition: that a group of people could rationally create a government, rather than have something accidentally handed to them by history and tradition. The Constitution certainly bears the scars of that creation. It’s the result of long and often bitter debate, less a single unifying vision than a multifaceted set of compromises and educated guesses at what might work. There’s a tendency among certain groups (like those occupiers) to talk about the Constitution as this perfect blueprint for government. Where it all went wrong depends on who you’re talking to — the 14th and 16th Amendments are both popular candidates — but they think if you could just get back to what the Founding Fathers intended, all the problems with government in the United States would just melt away.

That’s plainly impossible. It isn’t just that the world today looks vastly different than it did in the late 1700s. It’s not even that we can’t say what they intended, although we can’t; the document reflects the composite views of some 50-odd delegates. The core issue is that the Constitution isn’t what’s written on the paper. It’s our common, shared understanding of what it means.

It’s kind of like a recipe your grandmother wrote down for you. It’s got the ingredients and most of the steps there, more or less, but it’s weirdly overspecific in some ways (Do you really need Cool Whip Extra Creamy Whipped Topping?) and underspecified in others (What does “make pastry dough” mean?) and there’s a lot that’s just left out (This says add butter but doesn’t say how much). You know what it means because you learned it directly, but your children are going to learn it from you and their children are going to learn it from them, and eventually the alterations and substitutions and the notes that get jotted down in the margins (Dream Whip works fine; substitute blueberries if you want) become just as important — necessary even — for making the recipe work.

But that’s one of the problems we have in the United States. The country is divided between vastly different visions of what government is supposed to look like. The Malheur protestors are right that the way people understood the Constitution 150 years ago when all those ranchers carved up the land is different now. But most of us think a lot of those changes, like the 14th and 16th Amendments, are for the better. Essential, even.

The Declaration of Independence states power derives from the consent of the governed. But what does that even mean when the country can’t agree on the broadest questions about the role of government, or the relationship between the government and the people? How can you consent to something nobody can even articulate?

It’s been nearly two years since I gave up my apartment in New York City. In that time I’ve visited 38 countries, 22 for the first time. I’ve traveled by car and bus and boat and jet and train and, briefly, dogsled. I’ve taken off from an airstrip on the beach in a propeller plane that seated about a dozen people and I’ve sailed across the Atlantic on an ocean liner that carries 4,000. I’ve been north of the Arctic Circle and 100 miles from the equator.

For the past few months though, I’ve been stalled along with everyone else. I was stranded in South Korea for three months, alone, with no place to go. Most countries were understandably shut down to foreigners. I could have returned to the United States, but both the numbers and the news were constantly, horrifically dreadful. I thought a lot about the ethics of not going back, whether staying someplace with a low risk of catching the Coronavirus and an unburdened health care system was better than risking the vagaries of the public health system in the United States. I’m still thinking about it.

But the real stress has come from being isolated. I’ve been lucky to avoid having to shelter-in-place for all that long — Korea never resorted to a general lockdown like other places, and I arrived there before they were quarantining anyone from overseas — but it’s been nearly two years since I didn’t have travel plans. And with no plans, and no way to make any, I’ve been something of a nervous wreck.

I tend to get depressed. Back when I was stationary, I had three primary ways of dealing with it: I could spend time with friends, I could force myself to get out and do things, or I could curl up in bed and wait it out. I knew I was giving up much of my ability to socialize when I started traveling the world, and I’ve been more-or-less compensating just by having so much to do, with places I’ve never been, sights I’ve never seen, and a furiously dwindling bucket list. Being grounded has locked me out of a lot of that.

Another way of putting it might be I was starting to feel trapped living in the United States, locked in and held hostage by politics which felt like they had already started to descend into an sclerotic authoritarian farce. I had nowhere to go, but still felt like I couldn’t stay. Traveling was a way to escape, to try and get outside the system, clear my head, breathe some fresh air, and go looking for a new perspective. And when the global lockdown hit, all that got taken away from everybody.

The initial experience of travel is often one of shock. Everything is different: food, language, money, customs. People drive on the wrong side of the road, or ride tiny mopeds everywhere, or crowd around chaotically rather than queuing up. They eat disgusting things like grasshoppers or durian or marmite or peanut butter. You’re frequently jetlagged, out of sorts, struggling just to find your hotel and grab some food and recover enough from the trip to crash for the night.

Once you work through that bit, you start to see the similarities everywhere. Taxis work more-or-less the same the world over. Ditto museums, and hotels, and street vendors. You can travel from New York City to Morocco, to Istanbul, to Delhi, to Tokyo, to San Francisco and never eat someplace other than a KFC or a Burger King. One of the odd consequences of our interconnected world is that even cultural expectations are becoming globalized; there are reports of local criminals complaining about not getting read their Miranda rights, as a result of all the American cop shows being broadcast internationally.

Let’s call those the first and second order effects of travel. For most tourists, that’s as far as they get, noticing the vendor selling fried scorpions in front of the Starbucks and leaving it at that. And at that level, all differences are superficial. That’s actually not a terrible takeaway. Nationalism requires the demonizing of foreigners and immigrants and refugees, so a natural antidote is meeting them and realizing they’re fundamentally the same as you.

But there are third or fourth or even fifth order effects, the kind of things you only notice out of the corner of your eye at first, that become apparent after you make friends with the locals, start to frequent the same café for a few weeks running, even start to feel like you’re putting down roots. It was five years living in New York City before I could go a week without being reminded I was a stranger there, long past when I had memorized the subway stops home from downtown and could talk with some authority about the best pizza in the city. It’s only at that point where you start to understand the real, deep cultural differences.

In an emergency, all those differences become starkly relevant. We may all be wired into a single global economy, with access to what is largely the same music and movies and food and clothing. But even with that broad acceptance over the way the global economy fits together we’re seeing countries who have done well containing COVID-19 and those that have done poorly. And the difference doesn’t seem to be how authoritarian the government is or how wealthy the country is. It’s those deeper cultural questions, about how much to trust scientists or distrust the media, or how you balance risks to health vs. risks to the economy. If you’re lucky enough to live someplace that believes we all need to work together, you’re probably doing okay. If you don’t, well, sadly, you’re probably on your own.

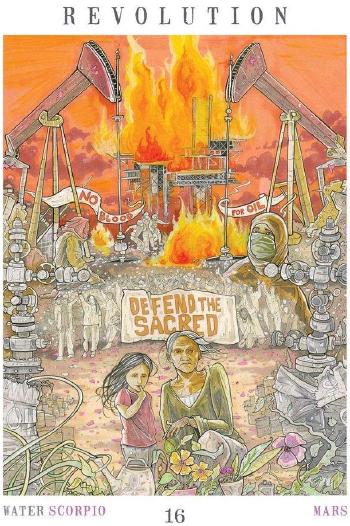

The big news in the United States for most of June was the protests over the death of George Floyd. I’m surprised this was the tinder that finally ignited truly mass protests; we’ve seen so many police abuses for so long it felt like nothing was ever going to break through. And suddenly, something did. For the first time I can remember there are widespread, multiracial demonstrations against the police all across the country.

Trevor Noah posted a video where he tries to put the protests in context. He frames them in terms of the social contract. We all agree to be governed by a certain set of rules — you can’t steal, or hurt others, or take justice into your own hands — and in exchange for giving up that power the government promises to treat us fairly. But it’s been clear from the very start that’s never been true, particularly not for minorities.

The protests are easy to understand from that perspective. If the government has broken the social contract, how else can the people make them live up to it? You can try to shame them into fulfilling the bargain, or make things so uncomfortable or inconvenient they’re forced to make concessions. And if all that fails and the people decide the system is still stacked against them, then what’s to stop them from lighting fires and grabbing as much stuff as they can carry? Why should I live up to my side if you won’t live up to yours?

The thing I’ve always found strange is it goes completely unremarked that no one ever actually agreed to that social contract in the first place. My citizenship was handed to me, alongside all these rights and responsibilities, from the moment I was born. I didn’t opt in. I didn’t get a choice. That’s kind of an issue for proponents of social contract theory; you can argue that by choosing to live someplace you’re implicitly agreeing to it, but most of us don’t have any place to go if we don’t agree. You can renounce your citizenship in the United States without having citizenship elsewhere, but those are the kind of decisions that wind up with you trapped in an international airport, unable to leave.

It’s hard to imagine a world before the current international order, without border checkpoints or passports. But in the 19th century, most immigrants arrived in the United States without official documentation at all. That only changed because of racism, the desire to restrict the number of Irish, or Chinese, or Jews who were allowed in the country. Border restrictions are always sold as security, but they’re inevitably used as tools of repression and control. Consider the reports from journalists being hassled by the TSA, or the increasing demands to turn over your social media history before you’re granted a visa.

We live in a world where capital can pass virtually unobstructed halfway across the world and back. Labor can’t. Some of us are already in a world where our livelihood isn’t anchored to our location. Most of us aren’t; we’re still tied down by jobs and family and limited resources. And if you’re stuck someplace gerrymandered, where they’re cutting social services and ratcheting up voter suppression tactics, you better hope the protests manage to change the world, because your ballots certainly aren’t going to be enough.

Last September, Thomas Piketty published Capital and Ideology, a follow-up of sorts to his surprise best-seller Capital in the 21st Century. His previous work was focused on proving that economic inequality was inevitably baked into global capitalism. His new one explores how we justify it.

In his telling, the age we live in is marked by “neo-proprietarianism,” an enshrining of property rights as a unimpeachable foundation of our economic system. This is, of course, how ideology works: it presents a set of interlocking beliefs so pervasive and all-encompassing as to disappear into the background. Ideology does more than shut down debate; it makes it seem as if there isn’t anything to debate in the first place.

I’m talking about questions like Can you own land? or Can you own air? or Can you own an idea? We’ve decided collectively through tradition and lawmaking and legal casework just what those answers are, what it means to own a song or a word or a tradeable pollution credit. But ultimately we’re the ones that decided we could. We can change our mind. We did, eventually, to such contentious questions as Can you own a person?

Piketty argues this ideology is used to explain why income inequality exists and more critically to justify why it’s necessary, even beneficial. There are other ways societies structure themselves — Piketty labels the feudal structure of clerical, military, and working classes “ternary society” as opposed to the current “ownership society” — but they almost all serve to explain why those who have wealth and power deserve it, and why those who don’t, don’t.

It’s all too easy to take the world we live in for granted, and accept the way things are as some kind of natural laws or at least essential components of modern life. That’s why it’s ideology. But it all reminds me of the Gnostics, who believed the physical world was a veil of misdirections, if not outright lies. There are other ways of understanding the world, other values we could be privileging. What if we decided property wasn’t sacred? What if we decided to organize ourselves around our shared humanity instead?

That probably sounds like some kind of hippy utopianism to a lot of people. But we’re increasingly seeing productivity become decoupled from wages. As more and more work becomes automated — 6% of the jobs in the United States are related to trucking, and we’re already on the cusp of having self-driving fleets of trucks on the road — we’re going to have to reconsider the way the world works.

The solution Piketty advocates is a significant increase in taxes, coupled with “a universal right to education and a capital endowment, free circulation of people, and de facto virtual abolition of borders.” And if that seems unlikely given the current world order, well, he argues for the elimination of nation-states as well. I guess if you’re going to swing, you may as well swing for the bleachers.

I eventually had to leave Korea, because my visa was only good for three months. I ended up heading off to Ireland, where I’m staying with friends. The immigration officer dressed me down for having the audacity of traveling at all rather than returning to the United States, scrolled through my social media chat to see if I was lying about having friends, and then rather snippily granted me a total of two weeks in the country. As a traveler I would be expected to self-isolate for the entire time. But it turns out there’s a blanket extension for visitors in effect, so I have an extra two months on top of those two weeks to plot my next move.

After nearly four weeks of wall-to-wall media coverage of protests against the police we seem to swinging back mostly to coverage of the Coronavirus, and particularly the disastrous response to it in the United States. As should have been expected, lack of a national strategy coupled with decisions driven by politics and ideology have resulted in the collapse of what limited gains had been made in the first place. That doesn’t mean the protests are over, only that they’ve exhausted the media’s limited attention span. We’re going to have to keep fighting just outside of the spotlight.

There’s a lot of questions about what the world’s going to look like in a year or so, after an effective vaccine has been developed and the economic fallout is clear, once we’re through the election in the United States, and when whatever reforms the protests have inspired start to take hold. There’s some thought that businesses will have permanently shifted to working remotely, and the shock of the global shutdown coupled with a significant downtick in corporate travel will crash the travel market. The era of bargain airfare would be over.

I know there are people who are hoping that’s the case, to help the fight against climate change. And I really don’t think it would affect me all that much; it’d be harder to plan my hopping around the world, but if the cost of flying were to double I could just travel half as much. I still think it would be terrible if it happens.

If the past six months have revealed anything, it’s that whether we like it or not we’re living in a interconnected world. Pandemics don’t respect national boundaries, and even if the initial reaction involves shutting down those borders, that’s not a fix our intertwined economies will tolerate for long. We rely on one another, and as our problems become global — overpopulation, income inequality, and climate change among them — so must the solutions.

Obviously the less accessible travel is, the fewer people travel. I really do think there’s something you’ll never quite be able to grasp about other cultures without having your feet planted on their soil. For a country as large and distant as the United States those misunderstandings cause disastrous foreign policy decisions. We need more travel, not less, to act as a counterweight to that isolationism.

But it’s the political changes I find myself worrying the most about. It’s not even primarily focused on the US elections; the current president is a symptom of the rot, not the disease. As things open back up, there’s at least a narrow sense that things could be different. Trying to predict how, though, is a fool’s errand. There’s little doubt the supporters of autocracy and illiberalism will use the present moment to reinforce their isolation and increase their control. You can see that in the laws China just passed cracking down on the protests in Hong Kong, and in the United States’ withdrawal from the World Health Organization. But there’s hope as well, embodied in the now global Black Lives Matter protests.

The United States is still split into two roughly equal camps, each convinced the other is trying to destroy them. It seems clear from my perspective the right wing is contributing the lion’s share of the divisiveness with its increasing embrace of paranoia, conspiracy theories, and science denialism, but it’s not like the left doesn’t have its set of shibboleths and echo chambers. It could be the voting in November is the first small step towards calming the mood and healing those divisions, but I’m sure people were saying the same thing on the eve of Lincoln’s election.

I’ll admit, there’s a part of me that thinks breaking up the United States wouldn’t be the worst idea. I’ve had the sense for a while that it’s too big and too unwieldy for a single country. Having just one elected official for every 600,000 people seems like a guarantee of a government that’s unresponsive to the needs of individuals, beholden to corporate interests and lobbyists. And if we’ve lost the broad consensus of what a government is for in the first place, maybe dissolution is the right answer. That seems unlikely, but at one time, so did Brexit.

Early this year, just as the Coronavirus was spreading, I read the “Fractured Europe” series by Dave Hutchinson. I put it on my to-do list years ago and had forgotten the premise, so it was something of a shock when I finally got around to it. It’s set in a near future where a global pandemic and economic crash has caused the collapse of the EU. In its place, dozens if not hundreds of small breakaway republics have declared themselves across Europe; independence movements have been normalized to the point where it’s feasible for single apartment buildings to declare their autonomy and gain official recognition. The result is a patchwork of border control stations and hastily erected walls criss-crossing the continent.

There’s a dystopic aspect to that in the books, but it’s a minor one. Mostly it’s just a hassle, swapping passports and applying for visas and constantly explaining yourself to immigration officials. Maybe that’s the solution, if we can’t abolish nation-states outright: break them down into entities too small to do much harm to themselves or others.

It’s Independence Day back in the United States, so I suppose it’s the right time to be thinking about all this, about what the purpose of government is and how to fix it when it’s broken. Jefferson himself suggested tearing up the Constitution every so often and starting from scratch, famously writing “The earth belongs always to the living generation and not to the dead … Every constitution, then, and every law, naturally expires at the end of 19 years.” By any measure, the US is overdue.

But thinking about all this, I suppose I’m mostly a Hobsbawmian. History is determined by crowds, not individuals. None of us — not even presidents — have as much control as one might hope. We don’t make history so much as survive it; we are all caught up in its tides, and thus will always find ourselves washing up on strange coastlines.

I’m still in Ireland, self-isolating, prohibited from leaving the apartment for a few days yet. The EU released new pandemic guidelines for visitors at the start of the month; as a resident of the USA I’m presently barred from the Schengen area despite not having set foot on US soil since December.

But this, too, shall pass. I have a few months to figure out where to go next, and it’s possible the EU will revise their policy or some countries will choose slightly less draconian restrictions. I’ll find a place to visit, a border to cross, somewhere else to live while we wait for a vaccine. The universe is still an astonishing and rapturous place, even if the politics are not. And the day will yet come when the final restriction is repealed and we all emerge from lockdown, take a moment to look around, and step — once again — into the unknown.