Easter, 2021, Dublin

Apr 4, 2021

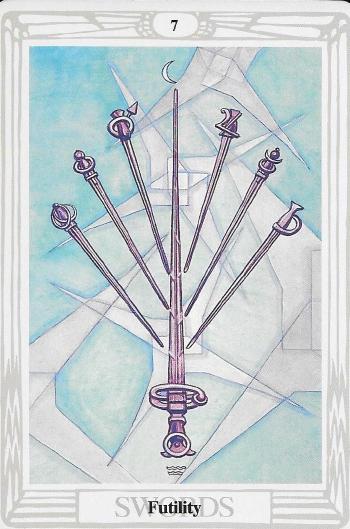

Lady Frieda Harris

I arrived in Ireland in June, 2020. I didn’t want to. I mean, I had to leave Korea after my visa ran out, and the United States was still recovering from a punishing first wave of COVID-19. I’d have stayed put if I could have, but I couldn’t. So when a friend offered an invitation for a safe place to crash for a couple months, I took it.

And here I’ve been, ever since. I took advantage of the summer and fall, when cases were relatively low, to do a little traveling around. But rising cases in October forced most of the country back into isolation, so I ended up back at my friend’s apartment. And even that didn’t last; they finished the semester they were teaching and ended up leaving the country, so I had to move out. I’ve been alone in Dublin in constant lockdown ever since.

This is, far and away, the longest I’ve spent in any single country since I started traveling. Second place is the 89 days I spent in Korea immediately before I arrived. Every other place has been 30 days or less. Excepting my erstwhile roommates, I’ve seen a grand total of one other person I’ve known since I arrived, and that for at most 24 hours. It’s a massive change from the life I’ve been living since I left the United States.

I don’t regret the decision to stay here in Ireland. Knowing what I know now I might have made different choices — rumor has it Thailand has all but reopened, with their quarantine policies keeping the infection rate low and the beaches free of tourists — but that’s all hindsight. I’m disinclined to do any sort of discretionary travel until I’m vaccinated, so I’m here to stay as long as I can.

But I wrote a year ago about how the world closing felt a lot like descending into Dante’s Inferno. And sure enough, we’ve been treated to a parade of horrors and grotesqueries. Now it feels like we’ve moved on, no longer quite in hell but still far from heaven, in the interminable numbness of Purgatorio. Vaccines are rolling out, case numbers are spiking, restrictions are being rolled back, and lockdowns are being reintroduced. Everything good and bad is happening all at once.

So I’ve been alone, doomscrolling in a series of rented rooms in Dublin. I’m anxiously and obsessively tracking the news on COVID-19 variants and vaccine rollouts and otherwise staring at the walls or trying to figure out how to stretch the 4 hours a day I’d like to be awake into the 18 hours a day I seem inevitably to be. I’m just trying to lay low until I can get the vaccine and the world calms down enough that I can start living again. And there’s nothing useful I can do to speed that up.

In a weird way, the pandemic forced everyone to live a lot more like I do: connecting with friends over chat or phone calls, collaborating through email or Zoom, spending weeks and months without seeing those we love in person. And I had already given all that up. I traded it for the freedom to travel. And since that’s been taken away from me as well, well, I don’t know what’s left. My identity is gone.

I am depressed.

Living through the pandemic feels a lot like grief, I imagine, for a lot of people. It does for me. There’s the constant unsettling mix of anxiety and boredom, the news from our friends and family who have been sick and suffering, and the unfathomable death toll creeping ever higher. We all lost a year of our lives, and most of us never managed to replace it. But grief is a process of healing. It’s necessary, to make our peace with the past, to mourn what we’ve lost and prepare to move on without it. Grief is a place you pass through. Depression is a place you live.

It’s important to understand I have always been depressed, since long before the pandemic started, like a low-grade flu you can never quite shake. People seem to have an emotional setpoint, kind of a thermostat, that they return to absent anything else. Mine is low. My serotonin reserves are perpetually overdrawn.

It took me a long time to realize I was nearly always depressed. It’s incredibly hard to imagine the world through other people’s eyes. And it’s terrifying to realize what seemed self-evident and universal — this is the way the world feels, most of the time, like it’s frequently a struggle to just sit and breathe and be — isn’t true for most people. For almost anyone in fact. The way you experience the world may not be unique, but you’re at least one of the rarefied outliers.

It’s not serious. At least, it’s not life-threatening. It’s more a pervasive miasma that seeps into the corners of everything, like underexposed film stock that bleeds black around all the edges. Or how about: like the world’s on a dimmer switch that’ll almost never go fully bright. Or maybe it feels like a radio with a broken receiver; no matter what the station is, whether it’s top 40 or jazz or talk or country, there’s always static in the background. Sometimes you get the signal dialed in. Other times nothing seems to work, the tuner’s shot, you can spin it all the way around and never land on anything but white noise cranked up to 11.

Before you ask, I’ve tried therapy and I’ve tried medications and I’ve tried them simultaneously. They sort of work — I fully and wholeheartedly endorse both — but neither work enough in my case to knock me much off my baseline. They’re life-changing for lots of people. But they haven’t turned out that way for me.

What kinda works for me is doing things. I ask myself what I would do if I weren’t depressed, and then I do it anyway. Pretending I’m happy goes a long way towards creating the conditions where I can be. I realize that sounds a lot like the terrible advice people who aren’t depressed are always giving people who are, as if you could merely think yourself better. I’m not saying that. And I’m not saying it works for everyone; if you’re too depressed to get out of bed — I sometimes am — no amount of willpower is going to help.

But there’s something about doing things, going outside and running errands and visiting friends and seeing new places, that does in fact work for me. It’s surprising how miserable I can be and still manage all that; it’s even more surprising to discover I’m less miserable as I get into the swing of things. It’s like a catamaran that’s always on the verge of being swamped until it gets up to speed. The more momentum you build up, the more you skim over the water, the easier it is to keep from drowning.

So, you know, I did that. I threw everything out and hit the road. And the constant necessity of planning places to go and visits to friends and cities to see has provided enough rhythm to generally keep my head above water. It’s exhausting and it’s lonely and it’s often bittersweet, but it’s not depressing. I may not feel entirely mentally well, most days, but things usually don’t feel bleak, as if it’d be just as well to stay inside and lie in bed all day.

Only now it really is just as well to stay inside and lie in bed all day. Safer and healthier, even. I’m immunocompromised from some of the medications I’m on, and at least borderline for a number of other COVID-19 complicating factors. I know I should force myself to at least go outdoors occasionally. But I’ve never been one for aimless walks around the neighborhood, and everything else I’d do to get out of my head is shut down: movies, restaurants, tour groups. Making up excuses to go outside feels like one of those “enrichment activities” where zookeepers hide food around the enclosure so the animals can get the ersatz thrill of hunting for it. I am a lousy zookeeper.

So I stay indoors and act like I’m depressed. And I am depressed, and everything I know that helps stave that off is stupid or dangerous or shut down anyway. So I’ve felt about as bad as I’ve ever felt for about as long as I’ve ever felt it, and like many other people for the last six months I stare at the walls, pick useless fights on the Internet, and hope the vaccine gets dispensed to everybody before we’re all dead.

There’s no good way to talk about any of this. Either you care about what I feel like, in which case I suspect I could trivially make you feel wretched in exchange for feeling marginally better myself, or you don’t, in which case I don’t want to talk to you anyway. The only thing I can imagine helping at this point is seeing people in person, in extremely small groups, and trying to relearn everything I’ve forgotten about travel in the past year. Which means the world needs to reopen. Which means I guess I’m going to have to stick it out and hope for the best.

Being stuck in lockdown in Ireland means I was trapped watching American politics — the election, the insurrection, the inauguration, the second impeachment — from far enough away to be personally unaffected but without any distractions to take my mind off the whole bloody business. At least I was with a friend for the election and the recounts. Not so after that.

I’ve spent some time on here talking about what it means to be a citizen, or an immigrant, or a expatriate. I’ve talked about what “home” means, and homesickness. And my life since late 2018 has been enacting the idea of stepping away from where you belong, in some sense, of voluntarily becoming a stranger everywhere you go. For me it’s all tied up with questions of identity — who am I, anyway?

I’ll always be American, in a lot of ways. It’s imprinted in the passport I’m carrying, the suburb outside of Cleveland I grew up in, and the fact I’ll miss New York City in my heart of hearts until I die no matter how often I make it back. But even deeper than that, the dreams and the myths of America are integral to the way I understand the world. The best parts, I hope: the belief that we are all equal, that we all deserve justice and freedom and dignity, that the ideals of fairness and democracy are and should be a fundamental human right.

But watching a right-wing mob storm the Capitol has reminded me of all the ways I don’t feel American. There’s a lot in the national psyche — a cult-like reverence for the trappings but not the substance of democracy, an inability to honestly face or address the mistakes of the past, a brashness that too often hardens into a stubborn incuriosity — that I simply can’t abide. And truthfully, those rioters were laying claim to a vision of the United States that’s as faithful to history as the one I hold. Probably more. The first president of the United States was a slaveholder. Even in the country that declared your right to liberty was both unalienable and self-evident, freedom has always been contingent.

I’ve been pessimistic about politics since the Clinton impeachment. You can trace the poison in the Republican party back a lot further — I think the real start of the rot was Nixon, along with Bork and the Powell Memorandum and a whole raft of venal, corrupt sycophants — but the Clinton impeachment was where the Republicans really committed to demonizing the opposition and winning at all costs to push through largely unpopular programs.

It’s too early to be writing obituaries for the Biden presidency, but my initial impressions are iffy. The Republicans seem to have closed ranks and doubled down on the extremist base of their party, which all but ensures partisan gridlock. Statehouses everywhere are passing sweeping new restrictions on voting. It’s possible the Democrats may yet throw out the filibuster or water it down enough to render it irrelevant, pass H.R. 1 and rollback some of the most egregious limitations, but even if they do future progress is going to rely on the Democrats moving in lockstep, and that’s not exactly a recipe for bold political action. And if the government doesn’t work — and the government of the United States currently doesn’t work — it’s fertile ground for insurrection movements, with one of the two major political parties openly courting them.

All of which is to say it looks like we’re continuing what was already a pretty rocky decade for democracy in the United States. I honestly don’t know how it’s going to turn out: if the Democrats can hang on through the midterms and win Biden a reelection in 2024, or if a third party actually organizes and becomes competitive, or if the various Proud Boys and Oath Keepers and white supremacists and sovereign citizens coalesce into an organized active paramilitary resistance movement. Maybe all of the above.

I’m already on record, at least half-seriously, in favor of disbanding the United States. I sincerely believe the political divisions carved into the country are just too great, and the risk of electing an authoritarian madman as the head of the military — one less feckless than the last one, anyway — is far too steep. But it’s hard to imagine a negotiated dissolution happening. And if political solutions can’t break through our divisions, people are increasingly going to try violent ones.

When I left three years ago, I can’t say I had all this in mind. But I had a inchoate sense of the possibility, even if I couldn’t articulate it. It’s one of the reasons I left. And now that a lot of my fears have been realized, and worse ones seem like plausible progressions, I’m mostly heartbroken. My first instinct is to get the people I care about somewhere safe, and I’ve tried, but I get the sense people just don’t want to deal with it. So my next instinct is to get myself someplace safe.

Since roughly the middle of 2020, I’ve been pursing a residency visa in the EU. It’s the backup plan, my acknowledgment that I’m really not ready to return to the United States and, even if I decided to stop traveling around, it wouldn’t be to go back. Getting the visa is a ridiculously torturous process — triply so during a pandemic — so it’ll take the better part of 2021 to get accepted, assuming it is. But it also means if things do go bad in the United States — really bad — I’ll have a place to land.

It’s scary. It doesn’t make much practical difference, really; I’ll still be residing in the United States and traveling under an American passport. But mentally, it’s another connection cut, another restriction loosened, another latch left unlocked. Sure, I can always come back. But after this, I wouldn’t need to. Ever.

It hasn’t happened yet. It won’t really change anything that wasn’t already changing if and when it comes through. I’ll still be me, whoever that is. And if the mere fact of travel does change who I am, that’s going to be true no matter what direction I’m moving in. I’ll just have to figure out who I am when I get there, along with everybody else.

I watched a little bit of Biden’s inauguration in January. I was looking for some promise that things would improve. I don’t know that I found it, but it was fine, I think. The truth is I’m simply not that moved by the pageantry of institutional power, all the solemn speeches and swearing oaths over historic Bibles and calls for greatness and reconciliation. I mean, if we’re going to have to have all the pomp and ceremony I’m glad it’s accompanied by poets and not military flyovers. But it doesn’t do anything for me.

As a corrective, I followed it up with videos of naturalization ceremonies for immigrants. If you haven’t seen any, I recommend looking them up. They’re almost universally abysmal quality, filmed on cheap videocameras with shoddy lighting and odd camera angles. The sound’s typically muddy. And the ceremonies are usually held in some of the most bland, utilitarian civic architecture you might imagine: dingy courthouses or cramped basements with threadbare carpeting and drop ceilings.

But they’ve also got people. All kinds of people. All applicants to become citizens of the United States. The USA doesn’t make it easy to become a citizen; most of the people there have spent years working their way through the system. The ceremony always seems a little rote, a little perfunctory. There’ll be a civil bureaucrat leading it. Nobody’s dressed especially well; you see a lot of sweaters and reading glasses. But the applicants? They’re happy. You can see it on their faces. And you can watch them smile and celebrate and cry as they recite the oath of citizenship.

That’s the America I want to be a part of. That’s the future I want for the country.

On Easter Monday, 1916, about 1,200 members of the Irish Volunteers and the Irish Citizen Army mustered around Dublin. They quickly took over most of the city center, setting up roadblocks, building barricades, cutting communication links, and digging trenches through St. Stephen’s Green. They didn’t have the soldiers necessary to hold out for long; by the week’s end the Easter Rising had been crushed. But the British overreaction and crackdown afterwards led directly to Sinn Féin winning a landslide victory in the 1918 general election, and that led to civil war, and that led to the establishment of the Irish Free State.

So I’ve spent this weekend thinking about two failed insurrections, one months old but thousands of miles away, the other all around me but finished a century ago. We’ve had the deaths and the carnage, we’re ostensibly through the worst of it, but I can’t help but feel we’re living through that moment of unholy calm after an unexpected gunshot. We’re holding our breath, waiting for the page to turn, for whatever is gestating to finally spring forth. I should have expected to get trapped in a Yeats poem if I stayed in Ireland too long.

So it’s Easter, a season of hope and rebirth. But it’s just too soon, this year; the seeds are planted but yet to bloom. They’ve extended my permission to remain in Ireland until September; I suspect I’ll get on a list for the vaccine in a month or so. I’ll be on my itinerant way again soon after that, once whatever the world is becoming has germinated.

But that’s the future. Not now.

For now, I am still dead, and not yet risen.