Birthday, 2023, London

Jul 14, 2023

Nearly five years ago, I left my home in New York City, packed up or threw out nearly everything I owned, and started traveling. In a better world it’d be exactly five years, I’d have left on my birthday and I’d be hosting a party on my birthday and everything would have lined up in a way my latent OCD would find deeply satisfying. Life rarely works that way, though. Nearly five years sounds better than 59 months, so nearly five years it is.

So nearly five years ago, I left my home. I left my home because it no longer felt like my home. I felt increasingly like a stranger in my own country, and so I left to be a stranger in the countries of others. If home is where we can be most ourselves, then I have dedicated my life to being least myself. Maybe if I travel far enough, I can become nonexistent, dissolving into the background the way Tyrone Slothrop does in Gravity’s Rainbow.

That’s always been a fear of mine. I’m good at absorbing ideas and ideologies and repeating them back in interesting and novel ways. The term for this in AI is a “stochastic parrot,” a computer model that can string plausible and convincing chains of words together without actually comprehending them. If we understand ourselves through stories — I was born on Bastille Day, in the year of the Ox, under a gibbous moon — what does it mean if you’re particularly eloquent? I can tell you dozens of stories about myself. I’m not sure what makes any of them more real, more me, than others. I’m a syncratist at heart. I have the philosophical instincts of a decorator crab.

But for all I’ve borrowed, all the things I would never have come up with on my own — heliocentrism or quantum mechanics, for example — I do think there’s some set of core beliefs that’s entirely mine. You could possibly convince me the sun orbits the Earth, given the right evidence. You’ll never convince me that some people are made to rule over others because of their bloodline or genetics or wealth. There’s a chance, however slim, that I could become a geocentrist. There’s no chance I’ll become a monarchist.

One of the generally accepted marks of a healthy mind is the ability to change faced with new evidence. I’ve changed a lot of things I believed over the past five years. Travel does that, if you’re paying attention. But mostly I’ve thrown things out; I know less than when I started out because I’ve seen counter-examples and talked to people who disagreed with me. I’ve pared myself down. I’ve given up the luxury of a number of comforting beliefs.

Whatever’s left? This must be me. This must be what I stand for.

I’m a vegetarian. I’ve been a vegetarian now for longer than I haven’t, so it’s been one of the defining features of my life for the majority of it. And it has been a defining feature, in ways I couldn’t have imagined when I started. Food is integral to the experience of being human. We all have to eat. And even more than that, we use food to gather people together, to share our culture, to enhance or alleviate our love and joy and sorrow.

I wasn’t thinking about any of that when I became a vegetarian. It was my freshman year of college and I had enrolled in an ethics class. We were assigned an essay to read that laid out the moral argument against eating animals simply and clearly. In short, it’s immoral to cause unnecessary suffering. Industrial food production causes animals to suffer. We don’t need to eat animals to be happy or healthy. Therefore, it is immoral to eat animals. QED.

Even at that, I didn’t switch immediately. I thought about it for a few weeks, tried to find counterarguments which felt even halfway convincing. And since I couldn’t, I was left facing a question: do I want to be someone who believes they are acting immorally and just … does nothing about it?

So I stopped. I quit eating chicken and pork and fish and beef — anything that used to have a face, as Mr. Rogers once put it. In college that meant a lot of cheese pizza and vegetable egg rolls. Eventually I found the Indian restaurant on the edge of campus, which likely saved me from malnutrition. It’s gotten a lot better in the years since then; virtually every place has a veggie burger on the menu these days. But I got by.

When I became a vegetarian, I couldn’t have know what a profound effect it was going to have on me. There’s something about holding a moral belief that the vast majority of people disagree with that’s deeply alienating, especially when meat is so interwoven into most cultures. I grew up eating ham at Easter and burgers on the 4th of July and turkey at Thanksgiving. Rejecting that has a cost. You isolate yourself, no matter how polite you are about it.

I sort of thought the world would catch up to me. The logic still seems so simple — don’t cause misery — that I’m always a little taken aback by how slowly vegetarianism is spreading. Maybe this is simply the way societies change ethically. I still think it’s inevitable. Eventually there’ll be meat substitutes and lab-grown meat that’s indistinguishable from farmed meat, and then it’ll be cheaper, and then economics will do the rest. It’s just a lot farther away than I had hoped. The arc of the moral universe may bend towards justice, but it sure takes its own sweet time about it.

The important thing for me, the reason I’m telling you this, is that it’s taught me two things. First, I’ve learned I can stick with what I believe is right for a very long time, even in the midst of concerted opposition. Second, I know that I can and will change my mind, faced with convincing enough evidence. A big part of life is finding a balance between those extremes, being confident without being dogmatic, open-minded without being capricious. You have to figure out what’s important, and be prepared to let go of the rest.

Love is difficult. Not romantic love, the kind the ancient Greeks called eros; relationships might be hard, but desire is effortless. No, I’m talking about what they called agape, charitable love, unconditional love, a deep, abiding love for each and every being on Earth solely because they are a being on Earth. This is the kind of love that Christian theologians mean when they talk about God’s love for humanity, the kind of boundless concern for the well-being of others we’re often urged to cultivate but rarely do.

Love is difficult because people are capable of doing horrific things to one another, to the Earth, to everything living on it. It’s difficult because we’re instinctively selfish. It’s difficult because it takes effort to be mindful and extend our empathy to those who think and act in ways we neither agree with nor understand. It’s also necessary. If you read anything on practical ethics, you’re likely to come across the idea of “circles of compassion.” It’s been around for a while — as far as I can tell it stretches back to ancient Greece — but it gets invoked a lot these days. Albert Einstein succinctly explained the concept in a letter to a friend:

A human being is part of a whole, called by us the “Universe,” a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circles of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.

We’re naturally inclined to feel empathy for those nearest to us: our family and friends, maybe our neighbors or coworkers or people we see every day. Beyond that, it gets a little dicey. Most people feel a special affinity for people of the same nationality, or the same ethnicity, or those who share their dialect. And so it goes with whatever points of commonality we notice, whether that’s sexuality or social class, ideology or intelligence. We tend to like people who look and think like us.

The corollary is that we tend to dislike people who don’t. Our circle of compassion excludes those we feel don’t deserve the full measure of our empathy, the ones we can mistreat without feeling guilty. We look for differences and then we use those differences to justify discriminating against others. People don’t like the feeling they get when their behavior contradicts their values, and it’s easier to change the way you think than the way you act.

But despite all that, our circles of compassion seem to be growing wider and wider. The history of African Americans is proof of both how profoundly attitudes can change in society and how unacceptably slowly that change can come. But you can see appeals to expand our circles of compassion in all sorts of social justice movements, from trans rights to animal welfare to charities for immigrants and refugees.

And for me that work is all fundamentally the same. It’s learning to see ourselves in more and more disparate groups. I don’t think you can really support women’s rights without also supporting gay rights or worker’s rights or any of the other struggles for equality. You can certainly focus on one or two, or think the battle for one is more dire than another. But to support one while denying another — effectively setting a boundary on your circle of compassion — means you end up merely substituting one hierarchy for another.

That’s not the endpoint, of course. There’s still, you know, the actual liberation of disenfranchised groups to go once you’ve recognized the necessity. It’s at best a start. But if your first step is a deep and abiding empathy for all living creatures — love, in other words — that’s at least a pretty good start.

There’s been a number of recent stories talking about how tourism is destroying the world, how the sheer numbers of visitors to the Galapagos or the Great Barrier Reef or Antarctica is dooming those ecosystems. As a traveler I’m trying to at least ameliorate the choices I’m making, being a little slower and more deliberate about how I’m moving, prioritizing trains and buses where it’s at all feasible, minimizing or avoiding time spent in those places which are the most fragile.

The purest choice, morally, is likely settling down somewhere and never leaving. That doesn’t seem realistic for anybody, let alone myself. I read a recent interview with the artist Anohni, where they said “We’ve all been forced into these complicitous stress positions in relationship to consumerism, where it’s impossible to even eat food without doing harm.” That’s a good way to put it. Capitalism has us trapped in a situation where all of our choices — even disengagement — are ethically suspect. Our response can’t be to give up. At the same time, we need to extend ourselves the grace to forgive ourselves for all the ways we fall short.

I applied for Portuguese residency way back in 2021. That’s still ticking forward, at its impossibly slow pace. I had the final interview for it last October. The immigration lawyer told me it would take about three months from that point. It’s been seven, and now that we’ve hit July it’s likely nothing is going to happen until September at the earliest; everyone’s on vacation. There was a chance I was going to be able to announce at my birthday I was finally pausing for a bit. Five years of travel is a lot. But even if I had the permit in hand, I wouldn’t be ready. A year ago, I’d have had a chance to visit Porto and Coimbra and Sintra. Maybe I’d have found a place. Maybe I’d be planning on moving in, just for the winter, just to see how it feels.

Things didn’t work out that way. I’ve got a busy travel schedule through the rest of summer and autumn, culminating in that most ethically questionable of tourist activities, a cruise. I’ve justified it to myself. It’s a small boat as these things go, with less than 400 passengers. It’s also a vacation with my father, whom I rarely get to see. Maybe those are good enough reasons.

But there’s a subtle difference in the moral risk of travel and, say, vegetarianism. There’s virtually no environmental cost in a single person visiting the Grand Canyon. That’s nearly true of the first thousand, even the first ten thousand. But the Grand Canyon currently sees five million visitors every year. Unlike eating animals — even a single act of killing an animal bears a moral cost — the harms of tourism really only emerge in the aggregate. It’s like climate change; unless you’re a billionaire, your individual actions simply aren’t relevant.

These are collective problems. Solving them is going to depend on collective action. It’s going to require a lot of coordinated effort at all levels, in the face of concerted opposition, in order to avert disaster. And coordinated effort feels like it’s in very short supply these days.

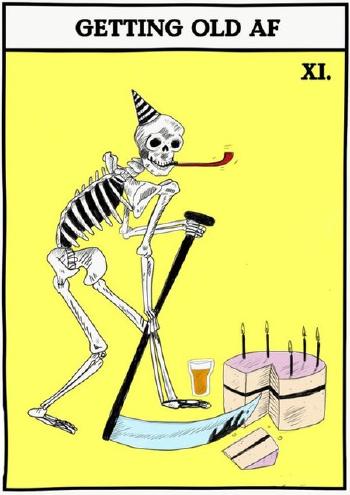

It’s my birthday today. I’m celebrating tomorrow. I’ve started throwing a kind of lavish party for myself every five years, once it was clear nobody else was going to bother. This year it’s a World War II themed perambulation around London built loosely around Gravity’s Rainbow. I tried to invite as many friends as I could think of. If you’re reading this and didn’t get an invitation it was assuredly an oversight, and if by some bizarre reason you’ll be in London on July 15th — maybe you live there — please reach out. We’ll have room.

I thought about standing up and giving a big speech, thanking everyone for coming and summarizing my last five years if not my last five decades. You might imagine I’d have something to say, some big announcement that I was settling down, or joining a circus, or had stumbled across a secret for long-haul zero-emission flights and would shortly be filing a patent. I’ve got nothing. I’d like to find a place to slow down for a month or two. I’d like to spend more time with friends, or have friends spend more time with me. I’d like a clearer plan for where I’ll be in a year, let alone five. I’d like a nap. Even with little to say, I’d get up and ramble for a bit if I had a magic ring for a proper exit. But I don’t have the ring on hand and it’s traditional to wait for triple digits. I imagine it’d be deadly boring anyway. Stemwinders generally are.

The latest season of The Bear came out about a month ago. The first season was good, great even, but the second one blows it away. It helps that the plot seems to overlap my life in weird ways; this season it’s all about opening a restaurant, so you get Chicago and food and fine dining and an episode set in a pastry kitchen in Copenhagen.

But it’s not really about restaurants. It’s about trauma, and the struggle to recognize and recover from it. It’s about the ways in which we find ourselves and discover who we are. It’s about how to build a meaningful life. And it’s about all the ways we help each other, the ways we have to help each other, the myriad acts of comfort and kindness and grace that let us get from one day to the next.

That’s what a restaurant is in The Bear. There’s a reason the process of getting your food to you is called “service.” A restaurant is a place where you’re welcomed and cared for. The show draws a connection between hospitals and hospitality; they’re both places separated from the rest of the world where you can rest and recover and heal, where other people will worry about you on your behalf. Working at a place like that is about putting the needs and desires of other people ahead of your own. We take care of other people, and trust that they’ll take care of us when we need it.

A decade ago I rented a big house in upstate New York for a weekend and invited people to hang out and play board games while I cooked for everyone. Five years ago I booked out a speakeasy and a restaurant for the evening. This year I rented a London rooftop and found a chef to cook a banana brunch straight out of Gravity’s Rainbow, followed by a day’s worth of events and culminating in dinner at a fancy restaurant. I’ve always made that connection between food and taking care of others. And life is ultimately about taking care of each other. What else could it be?

For my birthday this year I planned for 30 guests, but in actual fact we’re probably going to be about a half-dozen. I suppose it was always going to be a big ask; for most people it was a trade off between the money and the time and the travel. It hurts, but I know I’m nobody’s priority. That’s been the biggest disappointment of the way I’m traveling. People don’t visit. People don’t really even reach out much, or invite me to drop by for a few days. I’ve got a few friends I crash with when I’m passing through their cities and I’m always very grateful for that, but it’s different than spending a weekend in each other’s company. I need a confidant, not a benefactor.

Modern life has frayed if not outright severed most of the ways we used to build communities. Increased mobility, whether for jobs or education, means people often don’t have enough time to form deep friendships before they leave. Entertainment has shifted from groups to individuals: television instead of movies, video games instead of sports leagues. The internet and the rise of delivery services have removed the need to go outside at all. And social media, which once seemed like it would fill in those gaps, has been weaponized and used to drive us further apart.

So it’s not me alone. People everywhere are finding it harder to reach out and make connections, right at the moment where our survival as a species depends on it like never before. Auden wrote “We must love one another or die” and it’s true, it’s always been true, and I can only hope enough of us figures it out before it’s too late.

I’m just staying in motion, trying to see as much of what’s out there before it’s gone. Still trying to reach out to friends, to make connections, to kindle some kind of spark to ward against the darkness. I’m closer to settling down, I think, but not all that close. Maybe next year. And if you’d like me to drop by, shoot me a text. I’m happy to cook by way of thanks. I make a mean stack of banana pancakes.